Review: The Beginner’s Guide – What do creators owe their audience?

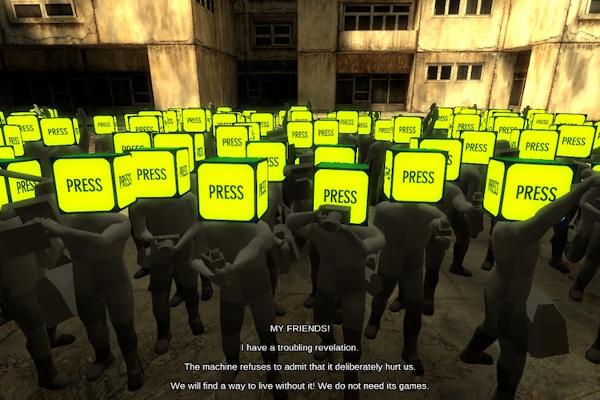

You can play The Beginner’s Guide in a couple hours, tops. Playing it feels unlike playing any game you’ve played, because there aren’t really objectives to complete or decisions to make and there’s definitely no way to win or lose. The most accurate description of TBG I could come up with is calling it the world’s first interactive critical essay on video games; a game built to explore what games mean to their creators and the people who play them.

The conceit is that the narrator (the maker of the “actual” game you’re playing) is taking you on a guided tour of a bunch of half-finished game ideas created by a fellow game designer he admires. The thrust of the conversation focuses on how games reflect the ideas and personalities of their creators. The biggest point of contention is this: creating for the sake of creating is a pure act — personal, private expression — and then once anything is shared with an audience, the work inherently changes. There are expectations the audience brings to the work, there are interpretations and assumptions made about the work, and ultimately a whole new set of demands made on the creator of the work.

The interactive mode of exploring this idea makes for a very novel, very engaging exploration of the creative process. I loved going on this journey. But I liked it most for being one big exercise in examining my relationship with any of the creative works I enjoy.

Does creativity inherently lose something when it’s shared? Does it require an audience, or change as soon as an audience gets involved?

For things you’ve made, how do you factor in the audience while making those things?