What is the cultural value of pop-up “Instagram Museums”?

As you can see, this piece is about what if it rained fruit, or something.

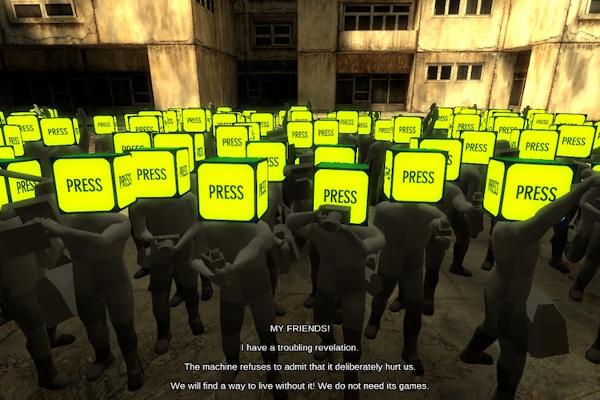

You’ve definitely heard of, possibly been to, and almost certainly seen a shared Instagram image from one of them: Museum of Ice Cream. 29 Rooms. Candytopia.

Amanda Hess of NYT visited them all, and wonders if they are less a new wave of artistic expression and more symptoms of existential despair:

The central disappointment of these spaces is not that they are so narcissistic, but rather that they seem to have such a low view of the people who visit them. Observing a work of art or climbing a mountain actually invites us to create meaning in our lives. But in these spaces, the idea of “interacting” with the world is made so slickly transactional that our role is hugely diminished. Stalking through the colorful hallways of New York’s “experiences,” I felt like a shell of a person. It was as if I was witnessing the total erosion of meaning itself. And when I posted a selfie from the Rosé Mansion saying as much, all of my friends liked it.

I visited one such place recently and had a similarly underwhelming experience; I captured some “cool” images, found most of the “exhibits” pretty shallow or only gesturing at depth, but found at least 10% of the experience thought-provoking. But then I thought, “Look at all these people enjoying this place and interacting with art, even if it’s mostly bad art. Isn’t that better than a bunch of people not interacting with no art at all?” Hence the question.