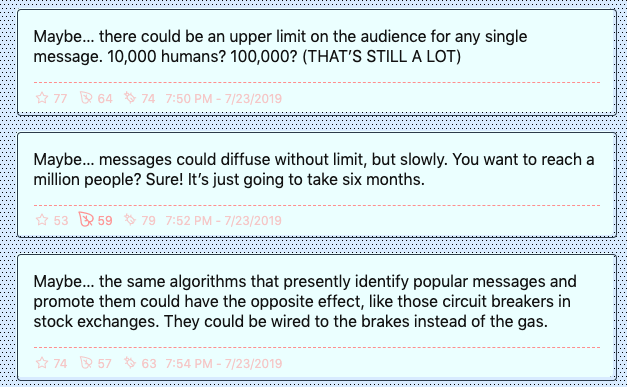

How do you deal with ‘algorithmic anxiety’?

Kyle Chayka in The New Yorker puts a name to something I’ve felt for many years while attempting to navigate the pervasive recommendation machines of the internet: algorithmic anxiety. As he relays in the article:

“I’ve been on the internet for the last 10 years and I don’t know if I like what I like or what an algorithm wants me to like,” Peter wrote. She’d come to see social networks’ algorithmic recommendations as a kind of psychic intrusion, surreptitiously reshaping what she’s shown online and, thus, her understanding of her own inclinations and tastes. “I want things I truly like not what is being lowkey marketed to me,” her letter continued.

…

Peter’s dilemma brought to my mind a term that has been used, in recent years, to describe the modern Internet user’s feeling that she must constantly contend with machine estimations of her desires: algorithmic anxiety. Besieged by automated recommendations, we are left to guess exactly how they are influencing us, feeling in some moments misperceived or misled and in other moments clocked with eerie precision. At times, the computer sometimes seems more in control of our choices than we are.

Personally, this means being afraid to ever ‘dislike’ anything on Netflix or YouTube, with the fear that anything remotely related will now be banished forever from reaching me, or hesitating to like even the most enjoyable clips only to be inundated with identical clones. I’ve begun listening to mid-tempo synth music as background while working, and though I still prefer energetic indie rock, Spotify has now almost completely shifted its picture of my tastes toward retro paradise vibes. It’s now become a side job simply to manage a computer-generated picture of who I am and what interests me.