How do subsidized lunches hurt cities?

If you help us build the tools that destroy democracies, the least we can do is buy you a sandwich.

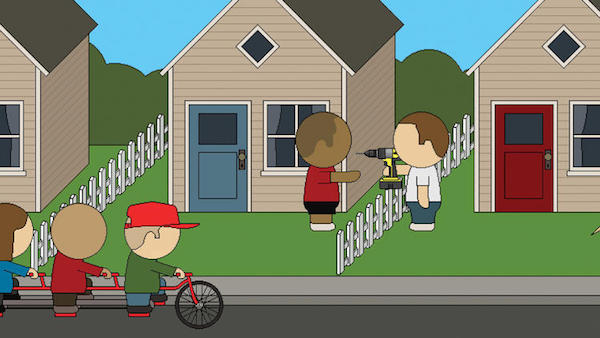

What was once a simple perk is suddenly a political statement, at least as framed by city supervisors in this piece on banning corporate free lunch policies.

“These tech companies have decided to leave their suburban campuses because their employees want to be in the city, and yet the irony is, they come to the city and are creating isolated, walled-off campuses,” said Aaron Peskin, a city supervisor who is co-sponsoring the bill with Ahsha Safaí. “This is not against these folks, it’s for them. It’s to integrate them into the community.”

…

“We gave huge tax breaks to revitalize neighborhoods,” Mr. Peskin said. “But instead, they’re all walled into their tech palaces.”

City lawmakers should definitely think of creative ways to ensure economic prosperity radiates outward from the biggest companies in town. Employees, rightfully, wonder if they’re at the losing end here.