Should progressives push for more corporate expansion in red states?

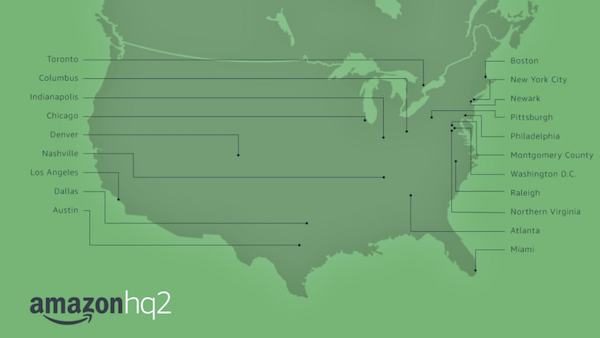

Above: list of cities where houses “with good schools, but you know, still near cool restaurants” are about to get annoyingly expensive.

This week, Amazon announced its shortlist of cities being considered for “HQ2”, their second giant corporate facility bringing tens of thousands of supposedly good-paying tech jobs.

Plenty can be argued about the vast tax incentives being given away to one of the richest businesses around, the propriety of a private company making municipalities grovel to be blessed with precious new-economy jobs — and we should have those conversations too!

But today I was struck by a more tangential thought about demographics. Several of these cities are in places that young, educated, progressive people (a.k.a. voters) are leaving in order to move to coastal urban centers that are already filled with other young progressive people like them — because that’s where the good jobs are. That migration is what’s throwing off the traditional balance of urban/rural, (a.k.a. progressive/conservative) in the states whose major cultural centers are on the decline due to industries shrinking or consolidating (particularly, say, Indiana or Ohio). One big company keeping more of those people in-state theoretically breeds other off-shoot companies, and helps keep the urban vs rural percentage in a state with only mid-size cities bluer.

Essentially, where Amazon places its second headquarters could literally swing a state, electorally.