Which apps manipulate you the most?

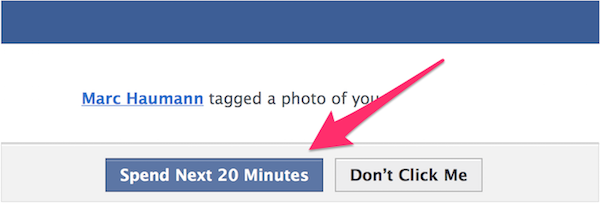

“I just HAVE to know which of my weird relatives thought that dog photo was cute.”

This Medium post from a former Google “Product Philosopher” (a weirdly pretentious title to be sure, but once you get past that he has a lot of smart things to say) on “How Technology Hijacks People’s Minds” is very much worth the 15 minutes it takes to read.

In it, he covers a handful of ways the web and mobile apps are designed to manipulate your choices and play on our human psychological weaknesses to keep you using them, or do what they want you to do vs what you may actually want to do, mostly without you even noticing.

A few examples: using Yelp to find a place to go after a movie will probably lead you to a bar or restaurant to spend more money, when a park bench could do perfectly fine. Notifications just vague enough to pull you back into apps for very little information, which leads to more news feed scrolling. Netflix autoplaying the next episode of a series. Even the basic principle of a menu forcing a choice between a few options they’d prefer you to take. Super interesting stuff we probably don’t think about much (*begin conspiracy voice*) because that’s exactly what they want.

Which apps or website do you think manipulates your choices or steals your time the most?

How aware are you of this as it happens?