Review: Sea of Rust – What will robots fight over once we’re gone?

Guys? Little help? Trying to maintain the primacy of the individual over here.

Lately I’ve been gravitating toward sci-fi stories, no matter the medium. The way good sci-fi focuses so clearly on asking an interesting question, then exploring the implications of the answers that come back… strikes some chord deep in my brain.

Looks at website description above.

Oh. Right.

Sea of Rust doesn’t strive for literary prose or nuanced character study. But it does explore a specific potential version of a post-humanity world with a surprising depth of thought and feeling.

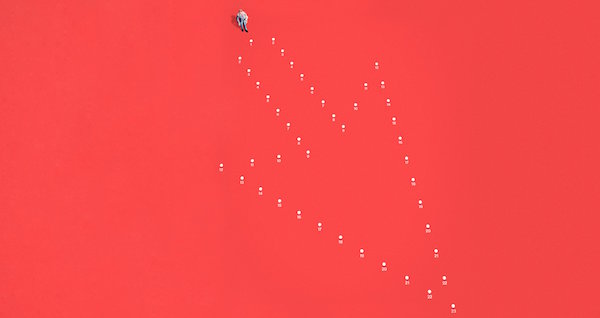

In this version, humanity created AI, and AI destroyed humanity. In the aftermath some AI are individuals, former servants or laborers scrounging for survival in a robotic Mad Max-style future. And they live in fear of hive-mind-style OWIs — skyscraper-sized “One World Intelligences” fighting to be the one and only being left on earth. OWIs want to subsume every other mind in existence; or use their mind-linked automaton armies to wipe out anyone who still clings to independence.

What it means to be an individual, what it means for a machine to have a soul, the long-term purpose of any “thinking thing” in the universe; these are big questions for a fun genre book full of robot gun fights. Instead of stopping at Terminator‘s Skynet, this book wonders what comes next when the artificial intelligences that outlive us start having conflicts among themselves.

What will the robots fight over once we’re all gone?

Is there anything essentially human they’d value enough to maintain in our absence?