To what degree should couples agree politically?

The battle of the sexes is over; they are clearly smarter than men.

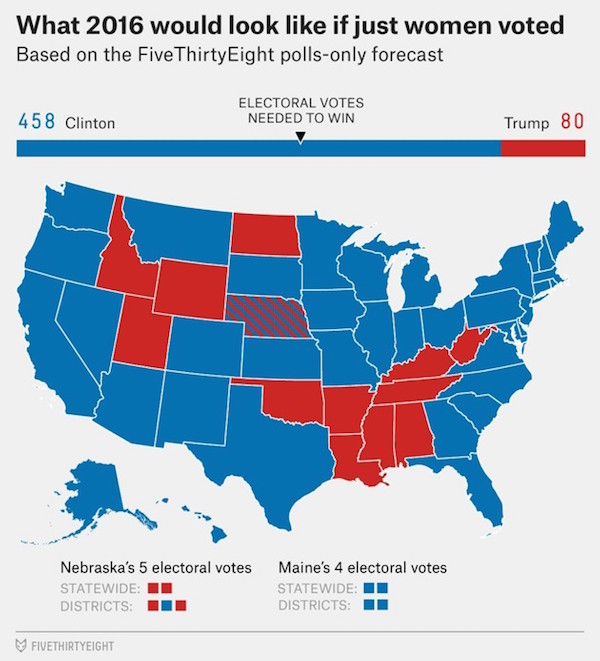

A quick, if loaded, topic as we approach the election: FiveThirtyEight posted data (above) showing that if only women vote, Clinton wins in a landslide. If only men vote, Trump becomes president. And this Atlantic piece shares data that the old truth that households, particularly married couples, tend to vote together is becoming less and less true.

How important is it for you to agree politically with your significant other?

What degree of difference is acceptable, or even beneficial? Where do you draw the line?