How has greater convenience made you more boring?

Eat it, Nike. Now, brands proudly appeal to the saddest parts of us.

Who among us isn’t guilty of posting the same verdict on the same tv show watched on the same service to the same social network via the same phone while ordering the same food through the same app sitting in your same comfy pants in your roughly-the-same furnished apartments.

It’s so easy!

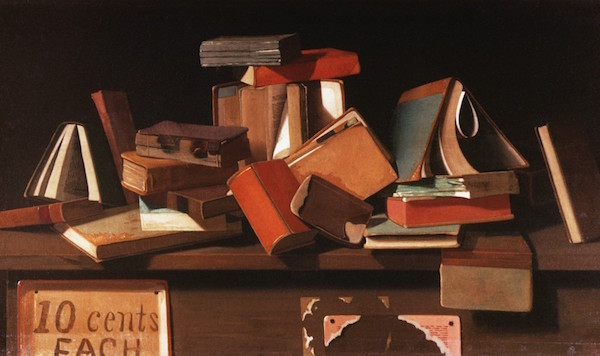

This piece on the tyranny of convenience takes a look at the trade-offs between convenience and meaningful effort, and raises some points about our choices worth examining.

Though understood and promoted as an instrument of liberation, convenience has a dark side. With its promise of smooth, effortless efficiency, it threatens to erase the sort of struggles and challenges that help give meaning to life. Created to free us, it can become a constraint on what we are willing to do, and thus in a subtle way it can enslave us.

Convenience, he argues, can be a trap. When the convenient becomes the unthinking default, it leads us to make the same choices, and in sanding off the rough edges of life, leaves us without texture.