Is turning your hobby into your career always a good thing?

A popular hobby for years, putting a bird on it has only recently become a viable career.

Now that life is so much easier than it was a hundred years ago — very few of us are farming 12 hours a day to feed ourselves — we’ve grown into a world where we don’t just expect to have a job, but have a job that we love. Turn our passion into our work. This Medium post explores the phenomenon:

With fewer reasons to stay in one job, workers began to explore a wider variety of options. For some, these options included turning a hobby into a business. Young people turned to what they loved, what they were good at, with an entrepreneurial mindset angled toward self-employment. It’s why we have so many artisan lollipops and food trucks.

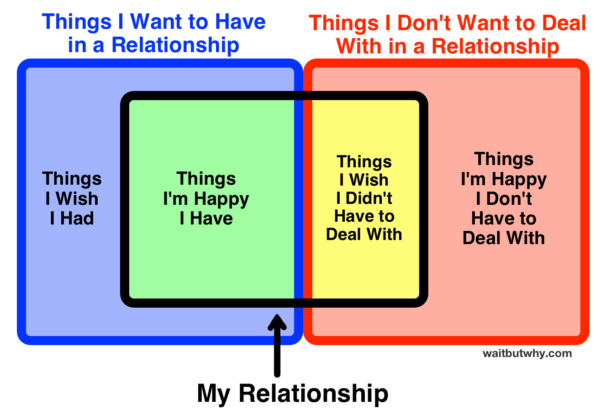

But the side effects are things like convincing yourself that turning your pass time into a second job is somehow noble. Or not really enjoying the thing you loved the same way you used to once you tack on the added pressure to perform, earn, or succeed.

What are the benefits and costs of turning a hobby into a career?

Have you ever wanted to try? What would you do? What stopped you?